Towards the end of his working days (late ’60s), Frank Carpenter suffered from poor health. Brazing up frames in the back room didn’t help. Often, these later builds were sub-contracted out to Colin Cape Cycles, the retail trading name of Swindon Cycles. Quite a few bikes from this period bear frame numbers prefixed ‘C’ or ‘CC’, it’s reasonable to assume these were examples of this.

The Carpenter marque still commanded respect. Finally, when winding down his business, Frank Carpenter sold the brand name to Swindon Cycles, probably with his stock of lugs and the all-important assembly jig. Carpenter race bikes thereafter appeared in Colin Cape’s sales literature, but this eventually just included a ‘Carpenter Olympic‘ model within their own range. Some were sold in the USA where Swindon Cycles had export connections. Some of Swindon Cycles frame building was in turn sub-contracted out to local one-man ‘shed’ builders. Quality control to Frank Carpenter’s meticulous standards must have become more of a challenge.

The Carpenter premises was sold when Frank retired, and continued as a bike shop for a while, selling the growing range of mountain bikes that were becoming available. Eventually that too closed. 52 Surbiton Road is now a letting agency.

Had Frank Carpenter not reached retirement age, would his bike building business have survived? Almost certainly not. He was a meticulous exponent of the craft of making precisely built lightweight cycles within the established pattern. Conservative, he was reluctant to follow the latest ‘fads’ let alone indulge in experimentation. Yet it was the disruptors that marked out the next phase of the evolution of competitive cycling. The era of the multi-purpose road/path/commute/tour bike was over.

1973 was the year of the global oil crisis. For the first time in decades the inexorable rise in car traffic paused. Britains transport planners realised that cars and lorries may not be the only consideration, rail and cycles had a role to play. All the same a shift in attitudes was a long time coming; after a brief pause the growth of car numbers continued. Traditional club riding was becoming more and more difficult to accommodate on our crowded roads.

In response thrill seekers established the BMX scene. Off road bikers escaped the car filled roads and quickly established cross country Mountain Biking then downhill racing. Japanese component suppliers like Shimano expoited this challenge; Campagnolo tried too late to follow the trend. Roberts Cycles addressed this market with their D.O.G.S.B.O.L.X. bikes; few other small builders did so.

Early ’80s. Vitus in France lit the fuse under an explosive era of fundamental innovation. They opened the doors for exotic new frame building materials. By 1983 Vitus frames, with lugged tubes made from Duralumin or Carbon composites were being successfully used by some professional teams. Steel tubing suppliers responded with new alloys such as Reynolds 753 and Columbus SLX.

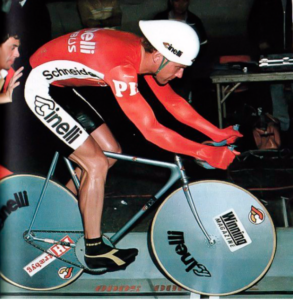

At the same time there was a growing appreciation of the importance of aerodynamics. Low profile geometry came in (even small front wheels) with bull horn bars to afford the rider support in these extreme positions. In 1984 On the track, Francesco Moser broke the mould with his outrageous big-wheel hour record bikes, lifting Merckx’s record beyond 50km. to 51.15

At the same time there was a growing appreciation of the importance of aerodynamics. Low profile geometry came in (even small front wheels) with bull horn bars to afford the rider support in these extreme positions. In 1984 On the track, Francesco Moser broke the mould with his outrageous big-wheel hour record bikes, lifting Merckx’s record beyond 50km. to 51.15

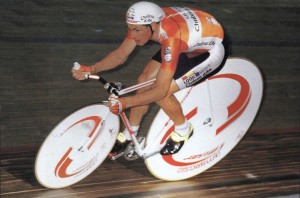

In 1986 Tony Doyle used all this growing understanding to good effect in his second world pursuit championships.

1987. The idea for Scott’s aerobars was Boone Lennon’s. As a coach of the US alpine ski team, Lennon was involved in wind-tunnel testing for downhill skiers, and understood the importance of aerodynamics. He was also a bike racer. Helped by engineer Charley French, he developed the first aerobar prototypes. Pro cyclists weren’t convinced. Triathletes became the first to pick up on Scott’s ‘Ski-bars’ which were soon dubbed ‘Tri-bars’. Many of them were using these bars in 1987 [such as Ironman legend Dave Scott] and their bike split times began to improve drastically.

Pro cyclists were more cautious, but once Greg LeMond had famously won the 1989 TdF with his last-gasp time-trial effort the new shape of bikes had been set, at least for TTs and endurance track events. Framebuilders such as Argos found the use of these bars actually needed a slight relaxation of steering angles to improve directional stability.

1987 Giant introduced the Cadex 980 C, its conventional frame geometry built with with carbon fibre tubing bonded into aluminium alloy lugs. They were starting where Vitus left off. It was just a start……

Brazed steel frames were still the order of the day into the early 1990s – but experiments with new materials like Frank Kirk’s die-cast magnesium alloy frames were underway. (It was very light, but to be stiff and strong enough it was cast with girder-section members which were about as aerodynamic as a cheese grater).

Mike Burrows worked with Lotus to build a monocoque carbon fibre frame for Chris Boardman‘s revolutionary 1992 Olympic-winning pursuit bike, the 108. But their efforts to commercialise the design were half-hearted.

Mike Burrows worked with Lotus to build a monocoque carbon fibre frame for Chris Boardman‘s revolutionary 1992 Olympic-winning pursuit bike, the 108. But their efforts to commercialise the design were half-hearted.

Giant snapped up Burrows and full carbon bike frames hit the market, soon to be mass-marketed in limited size ranges but several new configurations.

As a footnote, if Moser had broken the mould,  Graeme Obree, that brilliant maverick, challenged convention completely with his home made brazed-steel bikes and radical riding positions. Great for track racing and short, flat TTs but totally impracticable for anything else. In 1993 he took Moser’s hour record with 51.596km, only to lose it a week later to Boardman’s 52.270. His revenge? He eliminated Boardman on the way to the world Pursuit title later that year. In April 1994 he regained that hour record with 52.713) only to lose it again in September to Indurain’s 53.040).

Graeme Obree, that brilliant maverick, challenged convention completely with his home made brazed-steel bikes and radical riding positions. Great for track racing and short, flat TTs but totally impracticable for anything else. In 1993 he took Moser’s hour record with 51.596km, only to lose it a week later to Boardman’s 52.270. His revenge? He eliminated Boardman on the way to the world Pursuit title later that year. In April 1994 he regained that hour record with 52.713) only to lose it again in September to Indurain’s 53.040).

Big Mig rode a monocoque carbon composite framed Pinarello Espada. The writing was truly on the wall for the brazed steel race bike in spite of the fact that Stuart Dangerfield was riding a steel framed Argos bike in his 4th. consecutive 25 mile TT championship in 2003 The big-name producers were worried. How could they mass produce for a market fragmenting into so many different formats? Only the intervention of the UCI protected the basic ‘diamond’ frame shape brought in by Starley 100 years earlier. All the same the genie was out of the bottle. Bikes may no longer have been the main method of personal transport, but they met a multitude of different leisure pursuits, each with its own differing design needs.

So 100 years of painstaking steel-frame refinement was swept aside by a couple of decades of experimentation, innovation, new biking disciplines and new manufacturing techniques. The hundreds of small artisan builders had no answer to the new breed of mass-market producers with their multi-million pound investment in the tooling needed to make carbon fibre frames. Almost all closed (though Roberts survived until very recently). It is hard to imagine Carpenter would have been any different. The UK cycle-making industry is no more than a handful of specialist artisans now, a sad truth when GB riders dominated the Grand Tours for several years. and the last few Olympic cycles.

Where next?

After such a rush of radical improvements it would seem that another period of slow refinement must surely follow. But along the way, some of the joys of custom-built bikes have been lost. The whole business of buying a new race bike was once analagous to getting a new suit tailor made at Savile Row. Careful measurements, discussions about use “Road race, Time Trial or Track?”; “Grass track, cement or boards?” The debates about frame angles and dimensions. The choice of components, even the colour scheme. Is it possible these delights will be brought back to us by new manufacturing techniques like 3D printing of components, one-trip moulds and formers? Already Reynolds are showing 3D printed dropouts, formed from sintered steel, ultra-light yet robust. At the same time the UCI are cautiously relaxing some of the constraints imposed on bicycle dimensions and formats. New hour records have been the reward. Bradley Wiggins‘ 54.5km mark was more than double Frank Dodds 1876 record. His carbon composite bars were fashioned in custom moulds using 3D printing. It may well be that the period of innovation has not yet ended, new materials like graphene are appearing in bespoke carbon frames.

Carpenter Cycles may have held their place through a complete chapter of history, but that chapter is now closed; we march into the future without the scores of artisan steel-frame makers of that era. But they lit up the lives of generations of racers and earned our admiration.