Technology changes trigger social change. It doesn’t advance steadily. Disrupters – and disrupting natural events – challenge the status quo and establish a new order. New industries spring up to meet new needs. Old trades decline. Innovations in one field unleash others elsewhere.

In the case of the bicycle, this is comprehensively described in ‘Bicycle Design’ by

1815. Napoleon met his Waterloo. Elsewhere, in distant Indonesia, Tambora exploded. 100 cubic kilometres of muck were thrust into the atmosphere, including millions of tons of sulphur. Sunlight was impaired, summer temperatures dropped, 1816 became ‘The year without summer’, harvests failed throughout Europe. Starvation, epidemics and mass-migration happened everywhere. Short of fodder, many horses starved. Would fit young men have to walk everywhere? Enterprising cart-wrights started to experiment with 2-wheeled vehicles – ‘speed walkers’ or ‘velocipedes’ – but these needed reasonably good road surfaces. John MacAdam’s graded chipping materials were a revolution in the 1820’s. Daring velocipede riders found they could scoot along fast enough to take both feet off the ground.

Velocipedes with pedalled front wheels were the logical next step in the 1860s. Larger front wheels made higher speeds possible but still the machines were limited by their origins in the wooden technology of carts and wheelwrights. Then in 1869 Frenchman Eugene Meyer patented the wheel built with tensioned steel spokes. This abruptly propelled bicycle design from farmyard technology into the new age of steel. In 1870 the renowned velocipede racer James Moore brought a Meyer bicycle to England. James Starley immediately recognised its potential. He introduced his Ariel ‘Ordinary’ bicycle. He devised tangential spoke patterns to overcome the problem of the wheel twisting and spokes breaking under load. Much bigger driven front wheels were possible. Immediately, young bucks used them for racing. In one year bikes with 36″ front wheels were made obsolete by 48″ machines – which were promptly superseded by the biggest diameters that an athletic man could fit between his legs. Over 50″. Size mattered! What we now call ‘Penny Farthing’ bicycles had arrived.

Road improvements continued.  The Portsmouth road from the Angel in Thames Ditton to the Anchor in Ripley enjoyed a few years of fame as a mecca for cyclists throughout Britain and further afield.

The Portsmouth road from the Angel in Thames Ditton to the Anchor in Ripley enjoyed a few years of fame as a mecca for cyclists throughout Britain and further afield.

Only affordable to the rich, (and certainly not to the Carpenter family) ‘high-wheelers’ had but a short period of ascendancy. Meanwhile working men and women had to live, work and love within walking distance of their homes.

Henry Carpenter was born in January 1872 to William and Caroline in Islington.

In 1876 the first hour record was established by Frank Dodds at 25.4km. Try that on a ‘Penny Farthing’!

Then came another period of innovative disruption. In 1885 James Starley’s nephew John Kemp Starley introduced a radical new design that suddenly rendered those ‘Ordinary’ cycles obsolete. The key was the way he incorporated Hans Renold’s efficient roller-link chain into his design. Now drive was delivered to a 26” geared rear wheel. Other manufacturers were trying chain drives; it was J.K.Starley who had grasped the opportunity to drive the back wheel, reduce the size of the front wheel close to that of the rear, optimising its geometry for steering and control. No longer did the rider have to straddle an oversized wheel, simultaneously pedalling it and steering it. J.K. Starley’s “Rover” was safer, lighter, faster and cheaper. The bicycle we recognise today quickly emerged.

In 1887 the first three places in the inaugural Catford CC hill climb were taken by new-fangled ‘Safety’ bicycles – the days of the ‘Ordinary’ were over. Working men and women and the burgeoning middle classes could suddenly enjoy unprecedented mobility without the expense of owning a horse. A booming new industry of mass-producing manufacturers still left room for hundreds of artisan craftsmen to take up the opportunity. For the next 100 years, through two world wars, bicycle design and the whole industry went through a steady evolution. This lasted until a new generation of disrupters tapped into new technologies and a new emphasis on cycling as a recreation rather than utility transport. But that’s another story.

In the late 19th Century the interest in cycle racing exploded. On the continent the 1891 Paris-Brest-Paris race was won by Charles Terront on a Humber with the newly invented pneumatic tyres. As an impressionable teenager, Henry Carpenter would have seen the craze sweep Britain. Track racing grew dramatically as a spectator sport. Tens of thousands packed newly built velodromes. When a track was opened at Herne Hill in 1891 it was the eighth in London. Paced road races started to happen.

Ironically, attendance at track meetings slumped in the late 1890s. Track racing was hardly accessible to all. Bikes were now affordable to working people like William Carpenter, sales of bikes surged. Instead of paying to spectate the general public were now buying bikes and getting out enjoying the open road, many forming cycling clubs. The sudden appearance of large groups of cyclists on the road, especially racing men with their pacing teams, alarmed wealthy horse-owners. There were, after all, only 8,000 cars on all of Britain’s roads at the turn of the century against hundreds of thousands of bikes. Bike racing on the open roads in Britain came under real threat of being prohibited. In 1890 the National Cyclists Union felt compelled to ban racing on public roads. So, track racing flourished with new venues popping up everywhere.

Only F T Bidlake’s 1895 initiative to codify the secretive time-trialling discipline preserved cycle racing on Britain’s roads, and for the next 50 years ‘road racing’ in Britain developed in a very different way to the massed-start races enjoyed on the Continent. This had telling effects on British bicycle design, determined the different tactical and physical strengths needed by the athletes, and closed off all prospects of attracting commercial sponsorship beyond track events.

Only F T Bidlake’s 1895 initiative to codify the secretive time-trialling discipline preserved cycle racing on Britain’s roads, and for the next 50 years ‘road racing’ in Britain developed in a very different way to the massed-start races enjoyed on the Continent. This had telling effects on British bicycle design, determined the different tactical and physical strengths needed by the athletes, and closed off all prospects of attracting commercial sponsorship beyond track events.

Abroad, distance racing on the roads was permitted so flourished. In 1895 George Mills won the first Bordeaux-Paris race. The public appetite was stimulated. 1896 saw British riders continuing their success abroad. Arthur Linton won Bordeaux-Paris, his brother Tom was also a successful rider in the stable managed by the infamous doper “Choppy” Warburton. Frederick Keeping won silver in a 12-hour track race at the first modern Olympiad in Athens, Edward Battell bronze in the 87km Athens-Marathon-Athens road race. Objections that they had to work for a living so they “could not possibly be amateurs” were overruled.

Incidentally, in 1894, the first motor car race, Paris to Rouen, had been won by Compte de Dion’s steamer at 20 kph. with petrol driven Peugeots and Panhards trailing in his dust & cinders. These early cars were still slower than the 25km hour record set by Frank Dodds 18 years earlier.

It’s hard now to imagine just how much of an impact the cycling revolution had across the world. By 1898 the hour record had reached 40.8km. 6-day races had become immensely popular in the USA, with teams of 2 introduced for the first time to overcome the disturbing sight of doped solo-riders struggling on.By the way, these ‘bicycle-jockeys’ devised the ‘Jock-strap’ to improve their creature comforts.

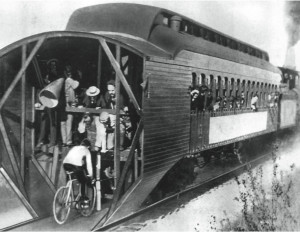

Deeds of daring-do continued to capture the public imagination. American Charles “Mile a Minute” Murphy risked life and limb to win fame draughting behind a steam loco in 1899. The observers grabbed him and his bike when he slammed into the back of the decellerating train. No Health & Safety inhibitions in those days!

Deeds of daring-do continued to capture the public imagination. American Charles “Mile a Minute” Murphy risked life and limb to win fame draughting behind a steam loco in 1899. The observers grabbed him and his bike when he slammed into the back of the decellerating train. No Health & Safety inhibitions in those days!

Superstars like Marshall “Major” Taylor earned the present day equivalent of $750,000 annually, many times more than the star football players

Superstars like Marshall “Major” Taylor earned the present day equivalent of $750,000 annually, many times more than the star football players

In 1901 Edgar Purnell Hooley chanced upon a short section of road surface where messy spilt tar had been covered with slag. The mixture had set to a smooth, hard waterproof surface surface that sealed the chippings. The next year he patented ‘Tarmac‘. Roads became faster still. Main stream cycle sport was free to break out from its purpose built velodromes.

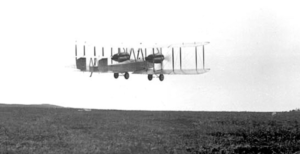

Bike  manufacturers attracted the most innovative engineering talent – no surprise then that in 1903 it was two cycle engineers, the Wright brothers who built the first successful aircraft. Orville’s first flight covered just 120 feet at 7mph. Bicycles were still far faster than aircraft!

manufacturers attracted the most innovative engineering talent – no surprise then that in 1903 it was two cycle engineers, the Wright brothers who built the first successful aircraft. Orville’s first flight covered just 120 feet at 7mph. Bicycles were still far faster than aircraft!

Meanwhile British riders enjoyed great success, from Mills in the inaugural 1891 Bordeaux-Paris to Leon Meredith, world motor-paced champion seven times from 1904-13. Bill Bailey, the Chris Hoy of his day, was world sprint champion in 1909-10-11-13 on a bike instantly recognisable today.Simple, single-speed bikes were the order of the day. Fine in towns or on reasonably level roads, but soon the question of gears cropped up. The early Tour de France racers changed gear by taking out the back wheel, turning it round and popping it back on using the cog on the other side. Butterfly nuts overcame the need for spanners. In fact, from its inception in 1903 until 1905 this was the only permitted way of changing gears.

Henry Carpenter started work with a walking stick manufacturer at the very beginning of this revolution. It is most unlikely he could have afforded a bicycle at first, but he was advancing his skills. By the 1891 census, at 19 he was recorded as a ‘Pipe Mounter’. By 1901 he had advanced to become a ‘Gold and Silver Stick Mounter’, fitting walking sticks and ceremonial canes with gold & silver handles. Howell’s walking stick-making factory in Old Street, Islington, was the largest such manufacturer in the world, employing over 450 men. Almost certainly, Henry Carpenter was one of these. He married Miriam on Dec 21, 1901, his son Frank Henry arrived exactly 11 months later, November 21 1902. By the 1911 census Henry had become a ‘Master Stick Mounter’. A picture emerges of a  master craftsman, dedicated to an exacting trade and steadily progressing in secure employment, raising his two young children (it seems he and Miriam had separated). Arthur Melbourne-Cooper’s 1912 film of Howell’s factory is here: http://www.eafa.org.uk/catalogue/215257

master craftsman, dedicated to an exacting trade and steadily progressing in secure employment, raising his two young children (it seems he and Miriam had separated). Arthur Melbourne-Cooper’s 1912 film of Howell’s factory is here: http://www.eafa.org.uk/catalogue/215257

Tour de France stages were inhumanly long – over 400km, but didn’t tackle the mountains until 1905. That was a great success, but hard on riders with such limited gear options! By 1911 variable gears were permitted, and in 1913 Sturmey-Archer hired superstar Lucien ‘Petit Breton’ Mazan, victor in ’07 and ’08. Sadly he was taken out by a dog while in the leading group.

The Great War brought this Edwardian era to a sudden close. We don’t know what work Henry Carpenter did during the War, but for sure it would not have been the decoration of walking sticks! At 42 in 1914 he was too old to be called up, his son at 12 too young. Most likely, as a master craftsman, he was drawn into the manufacture of equipment for the forces. What we do know is that after the war Henry was confronted by a personal crisis. The demand for elaborate walking sticks had fallen into terminal decline. Job losses across that industry were severe. Henry Howell’s business was contracting quickly, eventually closing in the mid-30s.

In contrast, the market for bicycles had taken off again. Big names grew rapidly with a burgeoning mass-market. Raleigh, BSA, Saxon among them. But competitive cyclists were eager for any marginal advantage. Scores of skilled artisans were drawn to this expanding industry, starting up small businesses building bespoke lightweight bicycles. No expensive machinery was needed to set up as a cycle manufacturer: just a hearth, jig and brazing skills for frame building, plus an intimate knowledge of what competitive cyclists wanted. Reynolds and Accles & Pollock supplied sets of tubes to make the frames; foundries cast lug sets; component suppliers like Chater-Lea, Leon Meredith’s Constrictor, Baylis-Wiley, Williams and Brooks standardised their fittings and screw threads. Small builders could offer customers a wide choice and respond quickly to the developing fashions of the growing market. But make no mistake, this was a highly competitive industry.

After the Great War, Desgrange insisted on a return to single-speed bikes in the Tour de France. This was to be a test of men, not machines. So it remained until 1937, this was the only way of changing gear permitted in the Tour de France. Arguably, this slowed the development of derailleur gears. It didn’t matter so much in Britain, with racing confined to flat time-trials, derailleur ‘dancing chain’ gears were seen as devices to fit to touring bikes and tandems. Race bikes were single-speed fixed, and that was that.

On June 15 1919 Captain John Alcock and Lieutenant Arthur Whitten-Brown landed with a hefty bump in a bog at Clifden, Galway, Ireland, having set off from Lester’s Field, St. John’s, Newfoundland. They had made the world’s first first non-stop transatlantic flight. The intrepid aviators flew a Vickers Vimy IV WW1 bomber, built in Weybridge from wood and canvas and powered by two Roll-Royce Eagle engines. From time to time Brown had to crawl out on the wing to de-ice the controls and carburettors. It had taken 15hs 57 mins of flying time, at 115mph. Their first interview was to a local newspaper. By the next day their achievement was front page news in New York and London. Neither was quoted as saying “One small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” But it was.

On June 15 1919 Captain John Alcock and Lieutenant Arthur Whitten-Brown landed with a hefty bump in a bog at Clifden, Galway, Ireland, having set off from Lester’s Field, St. John’s, Newfoundland. They had made the world’s first first non-stop transatlantic flight. The intrepid aviators flew a Vickers Vimy IV WW1 bomber, built in Weybridge from wood and canvas and powered by two Roll-Royce Eagle engines. From time to time Brown had to crawl out on the wing to de-ice the controls and carburettors. It had taken 15hs 57 mins of flying time, at 115mph. Their first interview was to a local newspaper. By the next day their achievement was front page news in New York and London. Neither was quoted as saying “One small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” But it was.

Somewhere along the way (from his war work?) Henry Carpenter had acquired advanced brazing skills. His son Frank, now turning 18, is understood to have enjoyed competitive cycling, from which he no doubt established a first-hand understanding of the demands of clubmen – the ever-changing technologies, components and myriad details of bikes built for racing. It must have been an understanding that would command the respect of this specialist market. At the start of the 1920s Henry and young Frank had the confidence to set up business in Islington as Cycle Makers. In the place of walking sticks there was steel tubing, handles of decorated silver became painstakingly filed lugs. Their bikes were not basic utilitarian machines offered at modest prices. From the outset they offered only advanced lightweights pitched squarely at the demands of enthusiastic clubmen. They quickly established a reputation for meticulous workmanship, supplying bikes to elite athletes and discerning clubmen for the next 50 years.

Their story is neatly divided into the pre-WW2 years under Henry Carpenter in Islington, then the post-war years under Frank Carpenter in Kingston-on-Thames.